Latest Awards

Issue #19: Radio's Battle of the Century

I've just returned from the 2023 Hamvention, and it was a blast. Congratulations to over 700 volunteers for making this event truly unique. For me, I began my trip to Hamvention with a case of nerves, as I was to give a talk while there. But the attendees were terrific, my hosts (Chris N8PEM and Michael W8CI) were exceptional and the time was well spent.

During my presentation on radio innovation, I spoke about one of my favorite events in the history of radio as we know it, and I'd like to share that part of my talk in this issue of Trials and Errors. Please allow me to take you back a hundred years, to the days of our Grandfather's ham radio. Those were heady days when the technology was evolving, and radio amateurs cooperated with big-league radio corporations in order to accomplish what had never been done before.

This is the story of The Battle of the Century.

July 1921

July 1921

Tex Rickard was a fight promoter, gambler and speculator who earned a reputation in the early 1900's as someone who could make things happen. Often by sheer will, but sometimes through cooperation with or pressure on others, his intent was always to make a buck (a goal on which he generally succeeded). Rickard was a big gambler . . . he'd been known to have made fortunes and lost them. He was a huge success In the Yukon during the gold rush and built saloons and hotels, gambling away that fortune before coming East to New York and moving into sports promotion. "Tex" earned that nickname during his youth, when he and his family lived in that State. He had no formal education, and in fact started out as a cowpoke in his teens and built a reputation as a tough Sherrif in Henrietta, Texas. But his nickname stayed with him and served him well as he used it on the periphery of New York society.

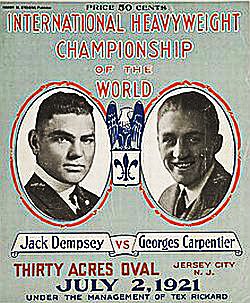

Europe was still smoldering three years later from the World War, and in particular, France. The WWI French hero, Georges Carpentier, attracted a good deal of international attention when he moved into professional boxing shortly after the war. He was the European light heavyweight boxing champion, and there was significant interest in Georges even from fans in the USA. This was despite the fact that the USA had the reigning world champion, Jack Dempsey.

Dempsey was a character with mixed reviews -- in some media referred to as a "bully," or a "draft dodger," while Carpentier was held up as a hero who had not only entered the war voluntarily but saved other soldiers' lives along the way. Tex Rickard succeeded in the negotiations to represent the two of these pugilists in a fight that he and the press would build into a major event. Carpentier was a great deal lighter than Dempsey, but was nimble, known to succeed because of his ability to bounce around the ring and throw jabs. Dempsey had years of boxing behind him and was a slugger whose ringside opponents tried to stay as far away as possible. It was a great match up, promoted by the Don King of the early 20th century.

The attention on this fight was such that Rickert had nowhere to stage the event as he expected to see a very large "gate," the boxing expression for ticket revenue. He tried to hold the big match-up in NYC but the NY Governor and local authorities stepped in and prohibited such a match in the State of New York. Rickard had to look to New Jersey, but there was no suitable arena to hold a crowd of this size. Originally expecting that the crowd size could be as high as 55,000-60,000, he began to build a brand new arena from green lumber on a tract of land called Boyle's Acres right across the Jersey border. As anticipation for the fight grew, Rickard gambled again and increased the size of the stands to hold 90,000, which made this octagonal wooden structure the largest arena in the world. Over 2,250,000 feet of lumber went to build this arena, which was torn down just a few years later. 500 carpenters with another 400 laborers were hired to build it through multiple contractors . . . it was a massive undertaking, completed in record time.

The attention on this fight was such that Rickert had nowhere to stage the event as he expected to see a very large "gate," the boxing expression for ticket revenue. He tried to hold the big match-up in NYC but the NY Governor and local authorities stepped in and prohibited such a match in the State of New York. Rickard had to look to New Jersey, but there was no suitable arena to hold a crowd of this size. Originally expecting that the crowd size could be as high as 55,000-60,000, he began to build a brand new arena from green lumber on a tract of land called Boyle's Acres right across the Jersey border. As anticipation for the fight grew, Rickard gambled again and increased the size of the stands to hold 90,000, which made this octagonal wooden structure the largest arena in the world. Over 2,250,000 feet of lumber went to build this arena, which was torn down just a few years later. 500 carpenters with another 400 laborers were hired to build it through multiple contractors . . . it was a massive undertaking, completed in record time.

In the 1921 wireless world there was considerable discussion amongst certain parties that the new technologies could and should be something more than point-to-point communication. Leading that charge was David Sarnoff, through the Radio Corporation of America. He believed in the concept of "broadcasting" but it hadn't really taken off. He appeared to be fighting an uphill battle, with zero support on this idea from the major players of the day. He needed a big win to bring wireless to the attention of the masses. (It was his intent, of course, to sell receiving sets or "wireless music boxes" to these new enthusiasts.)

Major J. Andrew White was the administrator of a little society based out of New York called the "National Amateur Wireless Association." He knew early on that the Dempsey-Carpentier fight could be the ticket to getting wider acceptance of new wireless technologies, but he needed an estimated $15,000 to pull it off. Upon approaching Sarnoff, he found a willing accomplice, but not his $15K. Sarnoff offered to put his own sweat equity into the project with the Association, along with less than $2000. White found out that money is not always as important as are relationships . . . Sarnoff was a connected guy, who went to the US Navy and asked to use a General Electric wireless transmitter that had been specially built under government contract (just over 3 kilowatts). They agreed. Now, all that was needed was a telephone connection between the new arena and the wireless station located a couple of miles away.

Amateurs Step In and Make it Happen

When the broadcasting station was given the go-ahead (and a temporary station ID, WJY) it was time to ask amateur wireless operators for their assistance. All over the Eastern USA, radio enthusiasts offered to help. They set up receiving stations and loudspeakers at theaters and in public centers where a modest admission charge was requested, with the funds going to two charities; one provided funding for France's recovery, and the other built a club for USA Navy men. And these amateur receiving stations weren't just in public places. As far as hundreds of miles away -- to the extent of propagation for this temporary station -- wireless enthusiasts put their gear on front porches and sidewalks. It looked as if it was going to have a huge audience.

And then, at the last minute, a tragic development. AT&T pulled the plug on Sarnoff and White when they announced that the telephone connection between the arena and the broadcast station would not be allowed. It turns out that the growing competition between AT&T and RCA for the wireless marketplace had resulted in ill will and a power play on the part of AT&T. Sarnoff, White, and their partners where devastated.

A wild idea came to the table, but it was one that they could pull off only with the cooperation of New Jersey. They would string up a temporary wired connection on their own, running wire nearly three miles from Boyles Acres and the new arena to the Navy transmitter. A test was conducted, and it worked. The plan was for Andy White of the wireless society to report from the fight location, and for a wireless operator at the transmitter's mic to repeat the words that Major White spoke as the fight proceeded.

The Fight

The Fight

The attendance was exactly as Tex had predicted. It was a total sell-out with nearly 90,000 fans attending at the Boyles Acres arena. The photo shows what was referred to as a mass of "teeming humanity," and something that certainly wouldn't have been allowed with today's safety regulations. It was sporting's first million dollar gate, with more than $1.5M in revenues.

Up and down the Eastern seaboard, radio amateurs succeeded in taking the General Electric transmitter's broadcast and making it public, to the delight of more than 300,000 in their respective audiences. It was a smashing success. While it wasn't a long fight, with Carpentier going down in the fourth round, it was long enough to establish wireless as something more than a point-to-point medium. It was the nation's first sports broadcast. Radio's trajectory after this huge promotion took off on a steep uphill growth curve, all due to the commitment of a wireless society, a group of hobbyists, a large corporation and a millionaire sports promoter.

Amateur wireless operators needed recognition and reimbursement for their troubles, and it was much like the incentives we have today in our hobby. They were provided with a nice certificate to hang on their shack wall, signed by a variety of notables, including the fighters, the US President, Tex Rickard, and Andrew White.

PS - The specially built Navy transmitter completely melted down and had to be scrapped after this event. Luckily, it lasted through all four rounds and died a few moments after Carpentier went down!

PPS - I forgot to mention in the article above that Dempsey and Carpentier became fast friends after this fight and for the rest of their lives they kept in touch. While they never fought again, they were mutually supportive of each other's matches and friends to the end.

Have a comment? See what others are saying now in our Forum discussion!

CLICK HERE and JUMP INTO THE CONVERSATION

|

|

Dave Jensen, W7DGJDave Jensen, W7DGJ, was first licensed in 1966. Originally WN7VDY (and later WA7VDY), Dave operated on 40 and 80 meter CW with a shack that consisted primarily of Heathkit equipment. Dave loved radio so much he went off to college to study broadcasting and came out with a BS in Communications from Ohio University (Athens, OH). He worked his way through a number of audio electronics companies after graduation, including the professional microphone business for Audio-Technica. He was later licensed as W7DGJ out of Scottsdale, Arizona, where he ran an executive recruitment practice (CareerTrax Inc.) for several decades. Jensen has published articles in magazines dealing with science and engineering. His column “Tooling Up” ran for 20 years in the website of the leading science journal, SCIENCE, and his column called “Managing Your Career” continues to be a popular read each month for the Pharmaceutical and Household Products industries in two journals published by Rodman Publishing. |

Articles Written by Dave Jensen, W7DGJ

- Trials & Errors #73 (Feb 7, 2026): Playing with Radio - February 7, 2026

- Trials & Errors #72 (01/19/25): Greetings from Outer Space - January 20, 2026

- Trials & Errors #71 (01/05/26): Mentors or Elmers? Optimize the Process - January 5, 2026

- Trials & Errors #70 12/15/25: General Electric and the Alexanderson Kidnapping - December 18, 2025

- Trials & Errors #69 (11/21/25):The Man behind AM Radio - November 25, 2025

- Trials & Errors #68 (11/04/25): The Value of YouTube vs. In-Person Elmers - November 4, 2025

- Trials & Errors #67 (10/10/25): Defending the Spectrum - October 11, 2025

- Trials & Errors Issue #66 (Sept 22 2005): High Water: Ham Radio's Role in 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami - September 25, 2025

- Trials and Errors #65 (9/10/25): Defining the "Spirit of Ham Radio" - September 10, 2025

- Trials and Errors #64 (8/24/25): Tech-Focused Hams -- A Shot Across the Bow to ICOM, Yaesu and More - August 24, 2025

- Trials and Errors #63 (08/10/25): A Digital Radio "Plug 'n Play" Experience - August 11, 2025

- Trials and Errors #62: Celebrating Radio Innovation and Innovators - July 27, 2025

- Trials and Errors #61: The Carrington Event -- The "What If's" of our Sun's Activities - July 13, 2025

- Trials and Errors #60: How Shorthand Moved from Telegraphy to Ham Radio - June 30, 2025

- Trials and Errors #59: Misinformation Surrounding the Origins of "Morse" Code - June 10, 2025

- More articles by Dave Jensen, W7DGJ...